The title here is misleading. George Washington was the super-palmerite of all time in the sense that BG John McAuley Palmer derived his theory of military organization from President Washington.

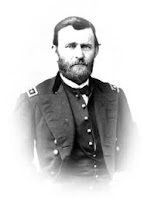

The title here is misleading. George Washington was the super-palmerite of all time in the sense that BG John McAuley Palmer derived his theory of military organization from President Washington. Nevertheless, he quotes U.S. Grant in what are breathtakingly Palmerite sentiments. Grant:

This state of affairs gave me an idea which I expressed while in Cairo [1861]: that the government ought to disband the regular army, with the exception of the Staff Corps, and notify the disbanded officers that they would receive no compensation while the war lasted except as volunteers. The Register should be kept up, but the names of all officers who were not in the volunteer service at the close [of the war] should be stricken from it.Palmer and Grant seem to see eye-to-eye on the central problem of the early war. Palmer:

The new citizen army of the Confederacy was trained and led by the Southern graduates of West Point and other officers of the old army who went South when their states seceded. As Grant said, "they leavened the whole loaf." But there was little such yeast for the Northern volunteers. Between January 1 and September 1 1861, 301 officers resigned from the regular army and almost all of these found important places in the Southern Army. By September 1 only 26 Northern officers held volunteer commissions. This was because all available Northern officers were needed for the formation of new regular regiments--too few and too weak in numerical strength to have any decisive effect upon the great issues of the war.P.S. On this Ash Wednesday, February 22, we have Washington and theology in one post. Here, we attempt to meet all your blog-reading needs.

The Northern war governors applied repeatedly for trained officers for their new volunteer regiments. But General Scott disapproved their requests because to grant them would injure his new regular regiments.

When you increase the regular army at the outbreak of a war you impair, if you do not destroy, its capacity to diffuse military knowledge and experience in the national citizen army. Until the close of the Civil War many educated Northern officers were kept as company officers in regular regiments while their Southern brethren held important command and staff positions. It was Grant's opinion that the marked Southern superiority in the early campaigns of the war was due to the fact that the North did have and the South did not have a standing army.

The pursuit of a false military policy is sufficient to account for the Federal defeat at Bull Run. While Jackson was hardening his citizen soldiers into an effective "Stonewall Brigade," his Northern brethren were busy increasing the regular army. In the words of the [Episcopal] Prayer Book, they had "left undone those things which" they "ought to have done" and had "done those things which" they "ought not to have done" and there was "no health in them."