4/28/2006

New blogging policy = old policy

The comments become lost and they tend towards Usenet-like or email-like interactions which makes for dissonance. I've noticed this on my fellow bloggers' sites, where I have left the occasional comment myself recently.

Having decided on no comments for this blog, it seems right to abstain from leaving comments on other people's blogs, which I will henceforth do.

I enjoy the comments on the other blog but if I don't highlight them in a post of their own, they constitute a sort of disturbing murmur. One odd thing I noticed - and these are generally artists, not readers - people there are more likely to leave comments on an old post than a fresh one. That, of course, makes it doubly invisible, because one does not re-read the old posts every time one checks in with the blog.

I really enjoy the yin-yang of co-blogging over there but that is something I wouldn't do here either.

The right way to blog seems to me to put your own views across - and to maintain a community dynamic by playing off the best ideas of other bloggers. On this last point I have been sadly remiss since August '05. My work life changed and I would like to do more of that when I can find just the right routine.

Thanks for reading, by the way.

This is the season for listening to the world's greatest piece of Civil War music yet composed: go hear Hindemith's Requiem for those we Love: "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd". I'll post on it soon.

4/27/2006

Book sales in 2005 - Battle Cry of Freedom

On the first, its commercial success as a midlist title tells publishers what their best outcome might be in backing a promising ACW manuscript. It sets the financial stakes for this kind of publishing. It also tells publishers what the successful form of a Civil War title should be: narrative, single volume, high levels of generalization, and recapitulations. TV tie in is a big plus too.

The second indication Battle Cry gives us is about the content of Civil War history. The mighty opinion-making machine built by Allan Nevins lost steam in the early 1980s. His magazine, American Heritage, had in two decades rolled off the plinth of a national readership of hundreds of thousands to the cliff edge of fiscal insolvency. The stream of successful companion military books it issued had also come to a halt. Its painstaking and strict editorial policies on the Civil War's historical questions could no longer be enforced from a strong platform that dominated Civil War publishing.

Into this early eighties scenario blundered an obscure race relations professor with very little knowledge of or interest in the Civil War. He clutched a commission from Oxford University Press - in a series edited by his former professor / sponsor/advisor - to plug the gap in a popular American history publishing series. He executed his commission by aggregating material millions of Americans had already read in American Heritage and in popular books by American Heritage's top article writers. His name was James McPherson, of course, and his book succeeded in aggregating Centennial output into a single tome, thus presenting one kind of compact retelling of the war to those working in other media:

James McPherson refers to a few of his many heavyweight predecessors in his Preface: Allan Nevins’s dual tetralogies, Bruce Catton’s three volumes on the Army of the Potomac and three-volume general history, Douglas Freeman’s four-volume biography of Robert E. Lee, and of course Shelby Foote’s classic three-volume, three-thousand-page narrative.It was this compactness with its level of generalization that attracted Ken Burns to Battle Cry. Another attraction was that it formulated information "people already knew" - a big asset in TV. Anyone reading Battle Cry when it first appeared had enough memory of popular Civil Warreading to experience a pandering effect, that warm sense of genius that comes from knowing everything the author intends to say to you before he says it.

Those watching the Burns ACW documentary likewise would be struck by their own immense knowledgeability, since everything presented was (to paraphrase John Y. Simon) the same bedtime story they had been reading for decades... a bedtime story that permeated nonfiction culture through the tremendous Centennial-era success of writers who came together in the pages of American Heritage.

The triumph of Burns' Civil War television series propelled the sales of Battle Cry - they were both complementary artifacts of the Nevins/Catton/Williams belief system - and they freshened the fading editorial lines that had held sway since about 1959.

From a position of publishing success, McPherson was able to review new thinking in Civil War history from the pages of the very best journals and newspapers; he could recommend like-minded reviewers to the lesser organs. He could recommend editors in scholarly publishing houses; he could blurb books meeting his approval; he could help projects with agreeable views; and as he came to head the AHA, he could name and influence prize committees. He had influence; he used it; and he was not open to revision of the work of 1960-1965.

Watching Battle Cry sales, then, tells us how much mileage is left in the idea tank of the Centennialmobile. Now that McPherson has given up Princeton University and a position of even greater influence - the AHA presidency - his ideas must move on their own merits, not through politics and influence. What that means for us is that when his book sales fall to a level that are no longer interesting to publishers, the magic fades and we are (at long last) on to the next thing.

I needn't tell you how eager I am for the next thing.

I go into this background at length because younger readers of this blog are like fish in the water - they lack a sense of the water itself and its peculiar qualities. In fact we have all been submerged in the "natural" sea of Centennial doctrine for so long it is difficult for the casual reader to distinguish between Civil War history and American Heritage editorial policy. This is the key historiographic problem addressed by this blog.

On to the numbers.

In 2003, The paper version of Battle Cry sold 548 copies through Ingram. Using the industry's rule of sixes, that translates into something like 3,300 copies through all channels (except libraries). At the end of that year, the odd project of an Illustrated Battle Cry of Freedom was released with the full fanfare of a new book - reviews, tours, ads, etc. The effect was odd. The old paperback version picked up sales (1813 books through Ingram in 2004; 1,777 last year) while the public showed little interest in the new picture book (77 copies through Ingram in 2003, 361 in 2004, 117 last year).

Illustrated Battle Cry was a commercial failure that did not make it to softcover (not as of this writing). It involved the safe exploitation of a name brand author and did poorly.

The same effect is found in new writing like the Gettysburg guide Hallowed Ground. We see a hardback but no softcover edition. Issued in May of '03, it sold 856 copies via Ingram that year and by last year Ingram sales declined to 348. These are healthy figures for university presses but seriously substandard for commercial imprints.

It is now unlikely James McPherson can get a publishing contract from a trade house - with the possible exception of his autobiography. (Witness his shaking down Gary Gallagher for a job with University of North Carolina Press.)

An additional difficulty for McPherson has involved the appearance of new media - suddenly book buyers could "talk back" to the professor and some of that talkback took the form of cruel mockery about McPherson's Gettysburg mistakes. (An author once confided in me about how down his publishers were on him because of the reviews left on the book's Amazon site. Are authors of McP's stature immune from that?)

At currentl levels, the Battle Cry is hard to figure. It was intented to be a textbook and is currently assigned reading across the land: can that account for much of the current 5,000 copy sales level? The performance of this author's ancillary output tells us yes.

The dam is breaking.

(Next: Stephen Sears in 2005. Backgound and industry info here.)

4/26/2006

Ending the war in 1862

Tim Reese was good enough to pass on this paper to me today by MG JBA Bailey: “Over By Christmas”: Campaigning, Delusions and Force Requirements.

... over the past hundred years military establishments, encouraged and directed by their political masters, have persistently underestimated the length and costs of their campaigns and have frequently had little idea of the actual nature of their undertakings.It's a sucker's game: the civilians ask for a military estimate and get one. They then enter into war - Politik conducted by other means - making a hash of the military estimate.

Politically-tainted overoptimism has often led to fundamental misappreciation of the nature of a military undertaking. This deficit in imagination and understanding is then, with some resentment, often blamed on “mission creep,” or explained away with clichés masquerading as alibis, asserting that plans “never survive the first contact” or that readily predictable consequences could not have been known in advance.Politicians hate plans and hate strategy. They are creatures of contingency.

... the serial misbehaviour of which defense establishments and their political masters have been guilty is so apparently irrational and foolish that it may in some way be endemic to the civil-military condition, and not amenable to correction by better training, education or more assiduous staff work.”McClellan's friend von Moltke the elder (above, right) noted: “when millions of men array themselves opposite each other, and engage in a desperate struggle for their national existence, it is difficult to assume that the question will be settled by a few victories.”

Unless you are a Civil War author.

There is a lot of George McClellan in old von Moltke, including the not entirely fair teaching offered the Prussian General Staff during his tenure that Grant's 1864 plans were simply a revival of McClellan's 1862 strategy.

I should note, by the way, that the business about no plan surviving contact with the enemy is pure von Moltke.

Meanwhile, Bailey has moments of optimism that surprise one:

The criteria for success in this complex battlespace must be headed by an awareness of the strategic environment, an understanding of the desired endstate and its clear articulation.Good luck with that, my friend. Desired endstates and clear articulation are not exactly stock in trade of the political class. I like it better when you say,

We are after all but actors in a long-running “human comedy.”A very dark comedy, if you are a soldier, sailor, airman, or marine.

Enjoy this essay by a British major general and understand - I am speaking as a former general staff officer myself - that no American soldier since McClellan would have dared write this piece.

4/25/2006

Nous on the beach

A respectful crowd at the Gallipoli dawn service was clearly conscious of being good on the sacred battlefields, after last year's controversy over litter, loutish behaviour and inappropriate music.

In other words, people had behaved as if it was America's Memorial Day. Says the governor general:

"We lost a campaign with 26,000 casualties, but had won for us an enduring sense of national identity based on those iconic traits of mateship, courage, compassion and nous," he said. "Let us never forget."

Nous! How noetic!

nous. mind or reason, both human and divine; intellect; "the place where the human ground of order is in accord with the ground of being"; the intellectual self

The governor general appears to be a reader of Eric Voegelin's metahistories.

4/24/2006

Psychological effects yielded physical effects

Younger soldiers who served in the U.S. Civil War and those who saw more of their comrades die were at greater risk for heart, stomach, and nervous illnesses decades after the war, reveals a study of individual and unit records of more than 15,000 veterans. [...] The medical histories and diagnoses were drawn from pension files compiled by government physicians to certify the veterans' health and disability status. Most of the other soldiers not included in the study were dead or deserters, and so lacked postwar medical records.I wonder if they considered the effects of living outdoors from 1 - 3 years, of not washing enough, of high risk of exposure to disease, of frequent dysentery, of poor diet, and of separation from family without leave for nearly the duration of the war, and of letters from home complaining of financial hardship with no chance of meliorating family circumstances..

(Some of this research appeared in February.)

How David Eicher lost the Civil War

A few years ago, in a newspaper review, I described my high hopes for astronomer David Eicher (right).

A few years ago, in a newspaper review, I described my high hopes for astronomer David Eicher (right).Like many people who come into Civil War history by reading Catton, Nevins, and other authors on the old editorial board of American Heritage during the Centennial era, Eicher regarded the various untold thousands of Civil War controversies as largely settled. The work, for new Centennialists, has been either to tell the story better; or to develop some biographical or unit history that strengthens the memes of 1960-65; or to explore underdeveloped subthemes.

What made David Eicher different from other young Centennialists was his fascination with dissonant minutiae – the odd factual material that if researched and studied ruptures the current consensus. He tended to use it to liven his narrative rather than pursue its implications, but at least he noticed it and was not afraid to handle radioactive bits and pieces. Eicher, unlike the general run of storytellers, was also detail-friendly, witness the tome he authored with his father. I hoped that he would cross over into a place where he need no longer square his conclusions with ancient editorial policies, where he would let the evidence lead him.

Eicher has turned away somewhat from McPherson and Gallagher – guardians of the old AH memes – he even names them here as examples of wrong thinking about how the war was won. But he has gone off the deep end, publishing a book that is overwhelmingly polemical in structure, despite the original research done for it.

Dixie Betrayed: How the South Really Lost the Civil War reminds me of a cruel remark Ralph Luker once made about Clayton Cramer: “... you begin with what you regard as a self-evident truth [and then] you clutch scattered droppings of evidence supporting your generalization…”

It’s as if the marketing concept for Dixie came first and the research came second. The thrust of the book is that “... a calamity of political conspiracy, discord, and dysfunction … cost the South the Civil War.” – Military Ink

“... the South was undermined by its paradoxical efforts to fight a war and retain state rights.” – Publisher’s Weekly

How was a nation built primarily on the concept of states' rights ever going to create for itself sufficient unity of effort to win a war the very purpose of which, from the Union perspective, was to ensure the preservation of the Union those states had pulled out of?” - Booklist

Is that the ring of a sound bite? If you think that this is extreme condensation on my part and unfair, gaze in awe at this interview. Eicher: "Lincoln maneuvered the right people into control with a different system that included such innovations as a War Board of hand-picked people he trusted. He went through generals in chief until he got to one he trusted, U.S. Grant, who he trusted and let go.”

Good grief. On what level does this statement work? It tries to compress the whole Union war effort into the management of one A. Lincoln. And it does terrible violence even on the terms it sets itself: the War Board, which lasted all of about four months, had no Lincoln picks on it – it was Stanton’s experiment and did not interact wit AL. The idea that Lincoln let Grant “go” is something Brooks Simpson and John Y. Simon have worked hard to change in the public mind for years, without result.

The generalization is wrong; its examples are wrong; it barely functions as "Won Cause" mythology.

If Eicher had begun work intending to fairly and open mindedly study the Rebel war effort, if he came to the conclusion his current book reaches, call the book “The Crisis of War and the Southern Government” or some such. Make your discovery while studying a broader issue.

I have no doubt someone could today write the same book as this based on the hypothetical defeat of the

David Eicher has the ability to publish history but chooses to function as a mere nonfiction writer.

4/21/2006

Smithsonian: the curator as dictator

Documentary makers seeking access to Smithsonian holdings must submit scripts for review and approval. The Institution reserves the right to disallow production arrangements and shoot the script itself, if it’s a good one. (Say hello to your uninvited production partner.)

The Smithsonian also reserves the right to prohibit access to the materials, based on what it sees in the script – or in case you refuse to partner with it.

Ken Burns, for one, doesn't like this. He thinks this gives Showtime, the Smithsonian’s partner, a view into other people's documentary projects. That's hardly my concern.

I see it as a move towards speech and information restriction. The Smithsonian's flack proudly boasts that "since the current process went into effect, 24 out of 26 projects have been approved." Put another way, in the last six months they have killed two projects that were none of their damned business.

4/20/2006

"Slaughter Pen" project

Tricord has purchased land associated with "The Slaughter Pen" at Fredericksburg at market prices when that land recently became available. Tricord is holding it for Civil War Preservation Trust, which has gone into overdrive to raise $12 million needed to gain title.

This is a very clean deal - the model of what preservation should be - leading to fee simple ownership and tourist boots on the ground. To donate, start at this page on CWPT's website.

- At the bottom of the page, you'll see a table with dollar amounts. Click one of them. Let's say you clicked $25. It will take you to a page called Donation Selector.

- You'll see an empty field for "Quantity." (This is confusing and why I wrote these directions.) Your quantity will be the number of donations you want to make. Enter the number 1. (This will eventually produce a result that is equal to 1 x $25.)

- After entering 1, click Continue.

- Donation Selector now displays a number of tables. The top table is labeled “Current Appeal”– look at the Total Amount column on the right – it should display (in this case) $25. Click Continue at the bottom of the page.

Let's encourage CWPT in this kind of battlefield preservation.

"Pulitzer-worthy" defined

Did I read that correctly? A new standard emerges ...

4/19/2006

New Gettysburg movie

The producer, a realtor, bankrolled the movie by selling a 42 acre Gettysburg lot to the casino developers - for use in the casino development.

He supports the casino.

4/18/2006

Second Manassas, the game ...

Wonder what traits Pope got stick with.

Hat tip to Brett.

Book sales in 2005 - the Grant bubble

Whether a non-trade house could have achieved the same sales levels for these titles without the advertising, publicity, sales force, and widespread book reviewing that trade sponsorship delivers is an interesting question.

If trade house resouces are needed to turn annual sales of under 5,000 copies per title, then the Grant vein may have been mined out. Keep in mind that all these titles were inteded to be blockbuster nonfiction breakthroughs. I don't exclude the possibility that there are 5,000 bookbuyers who will buy any and every hardback Grant title that comes out, regardless of publicity. That may be the lesson from this exercise in publishing overkill. Nor can I rule out the possibility of huge library sales, invisible to me, saving some publisher's bacon.

These Grant books, not incidentally, are bad books one and all. They add nothing to our knowledge of the man; offer no new interpretations based on old or new materials; and they content themselves with rehashing the old "Lincoln Finds A General" motif, so thoroughly exhausted by the Centennial era writers.

It's as if the major publishers noticed that Catton was out of print and decided to do something about it - other than bring Catton back.

One can hope a good Grant book would have done much better - Brooks Simpson is preparing a second volume to his biography, for instance - but this raft of reworkings and retellings has probably spoiled his chances for some time.

Josiah Bunting's Ulysses S. Grant was brought out in 2004 by Time and I would guess had a minimum print run of 15,000 copies . In 2004, Ingram sold 1,152 copies, which using our rule of sixes, translates into a total sales estimate of about 7,000 copies - under half of my guesstimated press run for this kind of book. Last year, in a fairly predictable decay rate, the sales were at half that, with the Ingram total standing at 649. Continuing on that trajectory, the print run will not be sold out.

Now Bunting was the strongest performer in this pack., followed by Edward Bonekemper (pictured top right) and his tome A Victor Not a Butcher released through the small but strong and savvy trade house Regnery.

Victor appeared in April 2004 and sold 832 copies through Ingram, which may represent 5,000 total sales. I thought it was something of a hit at the time. The print runs for Regnery are going to be smaller than for Time Books and Bonekemper was a totally unknown author when he signed this contract. My guess is that Regnery printed no more than 7,500 to 10,000 copies of the first edition. Last year Ingram sold 121 Victors, a steep drop. Regnery may sell out its first run if the sales decay slows but it seems unlikely.

Jean Smith's late 1990s Grant is still puttering along. Ingram sold 151 in 2004 and another 84 last year. Smith intrigued me by drawing our attention to Halleck's numerous efforts to replace Grant with Hitchcock and/or Buell but he irritated me by Goodwinizing sources (failing to cite or block quote many borrowed passages).

It's odd that Simon & Schuster would keep Smith's book off the remainder tables at current sales levels but Grant is of special interest to the chief editor of S&S, Michael Korda, who released his own Grant book in 2004.

A senior executive at S&S with the publishing company his to command, Korda was able to move a mere 558 of his own Grant units through Ingram that year - maybe 4,000 sales all told. Last year that figure dropped to 262 via Ingram.

One supposes that trade publishers will be revisiting the landmark years of 2004 and 2005 for a long time to come should anyone ask for a meeting about new Grant manuscripts.

On a happier note: where a Grant book deals in substance, its chances run much better.

Timothy Smith's Champion Hill, released via the small press Savas Beatie, sold 151 copies through Ingram in 2004 - the year of its release - reflecting almost 1,000 units from a brand new publisher. Last year Ingram says it sold 84 copies, reflecting about 500 hardbacks. If the press run was 2,000, this new title - on a start-up press - has a shot at running through its first edition.

I don't know what the budget is for Champion Hill, but the results look good to me. Let the wannabe retellers take notice.

(Previous post with many background links here.)

Pulitzer for Civil War novel March

Some new novelist had the awful idea of writing a sequel to Little Women - a pastiche in Alcott's style. This is the sort of idea you laugh about over drinks. or dream up in a freshman dorm party.

Some new novelist had the awful idea of writing a sequel to Little Women - a pastiche in Alcott's style. This is the sort of idea you laugh about over drinks. or dream up in a freshman dorm party.It won a Pulitzer for author Geraldine Brooks (right). We're talking about March.

From Amazon: "I think that if Louisa May Alcott were alive today, this is a book that she could have written, and I think she would approve of what Brooks has done."

I myself think of Alcott as being in a better place, if I can use such a tender, Pulitzer-worthy turn of phrase. I'm not sure she cares who is comandeering her reputation or spoiling the enjoyment of her novels.

At least one Amazon poster is unhappy: "I don't know how Ms. Brooks could take a high-minded chaplain, circa 1860, and turn him into an adulterer who 'married' his minister-sister's wife out in a tryst..." I know how: by following the advice of her editors and the conventions demanded of bus station literature.

Amazon also posted the inevitable: "Louisa May Alcott must be rolling in her grave."

I'm rolling in a virtual grave on her behalf.

4/17/2006

That mystery project

Do sign up for some copies.

Doctorow's March

You let a dreadful 1970s pop novelist loose in the fields of history and the results are going to be predictable. Tasteless self parody.

Art of the Confederacy

4/15/2006

A potentially useful series of books

Rather than correct any particular account of this or that campaign, or even a school of thought about a campaign, each book would divide a campaign into issues and problems, outline their difficulties and perhaps only briefly mention how this or that author attempted to resolve the matter. I'm not too sure about the last bit, because readers are defensive about their favorite authors and one wants the reader focused on issues of evidence, not to be distracted with worries over some writer's reputation.

Some problems addressed could be those of construction - showing how wide are the gaps in evidence over which literary bridges have been built to tell a story; plus problems of omission - descriptions of evidence generally slighted but necessary to understanding events; there are the tallies of materials known to be lost; there are those needed but supposed to be lost; there are the widely held facts that rest on a single uncorroborated source, and so on.

This idea came to me while reading criticism of this blog wherein people have apparently gone through three years' of archives and remain without understanding of my dissatisfaction with Civil War history. (My discontent is about evidence handling.)

To show, in a disapassionate light, the historiographic problems surrounding the rendering of a given campaign into "story" - will put people in the picture directly. They can then make their own judgements. And they won't have to pay the price in pain that the advanced reader paid as he made his way through a mountain of material one problem or contradiction at a time.

Now, if I take my own advice and make such a series available free, digital and searchable, on the Internet as a research aid; if I ensure it's indexed; and if I can do that in a way that the files remain available and accessible past the point of my death or loss of interest, I can have "failed better" as described in a previous post.

4/14/2006

Beatie, Woodbury and a mystery project

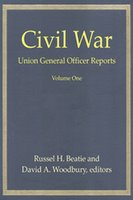

I was revisiting the Savas Beatie website late last night when I noticed a project by David Woodbury and Russel Beatie : Civil War Union General Officer Reports:

I was revisiting the Savas Beatie website late last night when I noticed a project by David Woodbury and Russel Beatie : Civil War Union General Officer Reports:In an effort to obtain a more complete record of the service of Union generals, the Adjutant General's Office requested in 1864 that each general submit " . . . a succinct account of your military history . . . since March 4, 1861." In 1872, a similar request was made for the last year of the war.Something bad happened to this publishing project, something setting it back - reading between the lines, I would imagine electronic storage media failure. David has not spoken of the project on his blog as far as I can tell.Of those generals and brevet officers who survived the war, 317 submitted reports. These priceless documents are published here for the first time (complete with a photograph, biographical sketches of each contributor, informative footnotes, and an index).

Again, reading between the lines, emails are needed to revive it and there is a link on the S-B page you can use to show a non-binding interest in the project, but let's cut to the chase:

sales@savasbeatie.com

Use the subject line: Civil War Union General Officer Reports

We need wider access to primary materials. Send an email, please.

Primary sources - all in favor, say aye

Primary documents are always the foundation of my research. I am known for turning up obscure published and unpublished source materials, and that's what I focused on for this book.

If that quote doesn't grab you, if it strikes a "yeah, yeah, okay" note, you haven't lately read any of the vast sea of Pulitzer Prize-winning history rooted in secondary sources. To paraphrase Tom Rowland (again), the deeper one goes into the material, the greater becomes the shock and personal fear at discovering how dependent one has been on other people's previous surmises.

The risk of not going down Eric's path, of trusting the previous treatments, is that you are made the fool by aggregating bad stuff. And that, in a nutshell, is the central problem in Civil War history today.

More on publishing this weekend

4/13/2006

I'll pass on this one

Swanson illuminates the characters of his story -- Booth and his co-conspirators, Stanton and his minions, Dr. Samuel Mudd and less well remembered supporting players -- with a wealth of personal detail usually found in fiction. He binds them to his narrative, which gallops along at the pace of a page-turning thriller. And even at the end, when the story barrels toward its well-known climax, the author ratchets up the tension of the final showdown in a Virginia tobacco barn.

Emphasis added.

Our nonfiction vocabularies are so impoversihed, we have to borrow terms and allusions from stage and literature to convey what is going on in a work of history. And yet, these terms convey exactly what is going on ... with the author.

Styple's good deed

4/11/2006

Book sales in 2005 - great expectations

The omission in today's writeup will be Doctorow's novel March. (Forgive me, I couldn't rouse enough interest to check the sales figures and if I had, I would not have known how to interpret them.)

Let me start with a book aimed at a broader audience than Ciivil War readers, one that had excellent reviews amidst wide press coverage and top notch product placement in chain bookstores: John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights by Whitman biographer David Reynolds. Issued in April by the prestigious trade house Knopf under its even more prestigious marque Borzoi, the book made a surprisingly lackluster showing in the first eight months of its debut, selling just 1,808 copies through Ingram.

If the publicly available Ingram figures are multiplied by six - the industry rule of thumb for guessing total sales - Mr. Reynolds saw about 12,000 books sold. On a trade scale, this is a marginal success. Perhaps trade scale does not apply to Borzoi - it may have dispensation to behave like a small press. Note also what one reader told me last year - that the Ingram rule of thumb does not predict sales to libraries and this is certainly a title for libraries.

Do you remember the press and hype surrounding Tripp's Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln? Released in January by Free Press, it had the entire year to rack up a Dec. 31 Ingram's figure of 1,686 copies sold, slightly less than John Brown which launched later in the year. I think that's surprisingly low, given the controversy about its content - I imagine that the extrapolated figure of about 10,000 in total sales is a serious disappointment to the publishers. The book may have suffered from what political consultants call "message rejection."

What would a 2005 roundup of ACW-themed pop-nonfiction be without reference to Goodwin's Team of Rivals? The book appeared late in the year - early October - and had just two months to collect its 2005 sales totals. I'll risk talking about the results anyway. Ingram sold 2,236 copies including pre-orders (I checked the pre-orders in August). Extrapolate that and you have about 14,000 sales at the peak of public interest in the Christmas season on a press run that must have been at least 250,000 copies for the first edition. Will Doris have to pay back some of her advance? How many more appearances on the Don Imus morning show will she need to sell that first run? Ingram is telling us "a bunch." We'll check in with her again in mid-2006.

These are three books that transcend Civil War readerships and I have chosen them to show that era titles with broader appeal are in as much trouble as Civil War titles generally ... more on which later this week.

Let me here digress briefly into the career of David Hackett Fischer who has been writing Revolutionary War pop history and who offers a point of comparison. In early 2004, Fischer released Washington's Crossing: at the end of 2005, Ingram's had sold 2,858 copies in hardback. There is nothing in Civil War nonfiction currently going that strong into its second year - not that I can identify. The paperback edition of his 972-page Albion's Seed, a book with no narrative and tons of analytical sociology, sold 908 copies through Ingrams last year. That's for a 1991 title focused on Colonial America. And that's more than half the annual sales level for McPherson's Battle Cry of Freedom (to which we'll return in a later post). Maybe it's required course reading but I like to think of it as my personal beacon of hope for readers sick of storytellers.

So we have a 2005 fireworks display that fizzled - the starbursts popped, hissed, and fell to earth.

On the fiction side, I think people expected Gingrich and Forstchen to do well with their ACW alternative history novel Never Call Retreat but that book did better than well. It sold 20,738 copies just through Ingram. That's putting the trade in trade publishing, by gum. Shaara the younger moved just 1,195 copies of Gods and Generals through Ingram in '05, a sharp decline from '03 and '04.. His late father continues strongly with 8,549 Ingram sales of Killer Angels. Both books have been out awhile and the earlier work of G & F is not sustating sales at these levels.

The all time midlist fiction champs, again by way of comparison, are Ayn Rand's novels and last year the Fountainhead, in paperback, sold 7,327 copies via Ingram. For Killer Angels to be in that sales league year after year is special.

(Later in this series I'll look at the fate of more "name" authors in 2005; the fate of the new faces; the outcome of the Grant publishing bubble; and I'll summarize some general ACW publishing trends since 1999.)

Related posts:

Amazon sales rankings explained

Amazon top sellers of 'o4

Barnes & Noble top sellers of '04

The 2004 sales overview is here and '04 series posts are linked at the bottom of this post.

My overview of the publishing industry is here.

Ingram numbers are explained in that overview post (above) and referred to here.

4/07/2006

Internet citations

Found this nice Web page that lists different citational style options.

Here's the Chicago Style that book publishers prefer:

1. Joseph Pellegrino, "Homepage," 12 May 1999, <http://www.english.eku.edu/pellegrino/default.htm> (12 June 1999).

They break it down this way:

Author's name

Title of document, in quotation marks

Title of complete work (if relevant), in italics or underlined

Date of publication or last revision

URL, in angle brackets

Date of access, in parentheses

That covers the bases, I think.

Unfortunately, web sites being as emphemeral as they are, you could be left holding onto a citation as worthless as "McClellan's letters to his wife" after a few years.

One key reason to use Blogger is that being a free service, the site will survive my death or disinterest for some time. Additionally, it is indexed and, I hope saved to a Google backup somewhere that can be retrieved in the future if needed.

4/06/2006

Connect the histories

I can hardly wait to read Sanjay Subrahmanyam's Explorations in Connected History coming out next month. This review in The Hindu is enticing: "enriches historical writing and contributes to historiographical advance," "new vistas of analysis can reveal different trajectories of history," "he situates micro-level developments in the larger context." Best of all:

I can hardly wait to read Sanjay Subrahmanyam's Explorations in Connected History coming out next month. This review in The Hindu is enticing: "enriches historical writing and contributes to historiographical advance," "new vistas of analysis can reveal different trajectories of history," "he situates micro-level developments in the larger context." Best of all:... adopts a very high level of methodological sophistication and nuanced analysis. They mark a significant advance in the historiography of the intellectual history of the early modern period.Subrahmanyam is reacting to the primitive state of South Asian history in a disciplined, creative way. Can his field be worse off than Civil War history? We read binary nonfiction: North vs. South. Military vs. Political. Social vs. Economic. Democrat vs. Republican. Land vs. Sea. It seems as if in order to transcend the binary pairing of topics in one book, a second or third book must be read.

On Civil War Talk Radio, I despaired of our writers reaching the level of a Geoffrey Parker, who covers in a single volume, 30 years of political, military, dynastic, geostrategic, colonial, and ecclesiastic crises. Meanwhile, we're stuck on "Is this a political or military study?"

Perhaps Subrahmanyam will surpass even such as Parker. Let's hope whatever breakthroughs Connected History holds, they can work for the worst kind of history as well as the best.

Gettysburg casino hearings

Washington Post - Scores of proponents filled the Student Union Ballroom on Wednesday, many wearing T-shirts with logos of betting chips that said "Pro Casino."

Gettysburg Times - Nearly 200 groups and individuals have registered to testify during the three-day hearing.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette - The three Adams County commissioners were split in their views on the casino. Republicans Lucy Lott and Glenn Snyder said it wasn't appropriate for "hallowed ground" like Gettysburg, and feared it would raise county costs for traffic control, police, fire personnel, and sewer and water facilities. Democratic Commissioner Tom Weaver sided with Mr. LeVan, seeing the casino as a way to increase tourism.

Associated Press - Gettysburg College students, parents, and professors testified that gambling is antithetical to the school's educational mission and the community's stewardship of the battlefields.

On Tuesday, Gettysburg City Council backed slots:

Associated Press - Gettysburg's borough council voted to support a proposed slot-machine gambling parlor near the historic Civil War battlefield in exchange for a $1 million-per-year revenue guarantee.

4/05/2006

Failing better - comments

That does not mean making every book digital - or every part of a book digital - it's more about the key findings and analysis being shared.

Eric is concerned about copyright - I do not back Google scanning books and then earning ad revenues for itself by displaying book content. That is piracy. And I do know that digital content can be copyrighted. Is digital work abuse proof? No.

Over the years I have shared a number of discoveries in this space. I will share more. If that material is retrievable to the public through keyword searches, I fail better than if I fail in commercial publishing. If someone claims what they read here as their own work, I don't care. If I did care, I could stand up for myself in the same way a print author would do so.

I read a book last night in one sitting - and I'm a slow reader - Lincoln's Tragic Admiral. That bio had no business being in book form. The author had to cover - no doubt for reasons of publishing economy - a 46-year Navy career in 200-odd pages. This Du Pont volume needed 800 pages minimum plus all the correspondence you could scan or transcribe. We need this scholar's best crack at a Du Pont bio, not what the operations department at his publishing house thinks it can affort to print and sell. What good is a 200-page bio of a Navy reformer and Civil War admiral, except as a story? I enjoyed the story. I amused myself for an evening.

That author needs to fail better.

Meanwhile, hat tip to Brian Downey, who is mentioning the post as well.

The impulse to write about failing better comes from compiling Civil War book sales data for scores of titles - 60 to 80 - twice a year and from analyzing seasonal publishing lists since 1997. I don't know of any other Civil War publishing sector analyst active apart from myself.

Have been in commercial publishing since 1974. Have published books; was editor-in-chief of a national magazine, 1986-1987; still collect royalties from an electronic newsletter I launched in 1983 with a 300 baud modem (it ran 10 years); freelanced for a trade newspaper for 11 years; told newsletter publishers how to improve content and increase circulation as a paid publishing consultant; have edited manuscripts; and currently earn my living writing.

That doesn't make me an industry guru worth reading; nor do I need to qualify my arguments with an appeal to authority; I share this only because new readers have said "Given that Dimitri has never gone through the process of publishing anything in the journal / magazine / book medium please explain how he can claim any insight into the relative merits of web v. book format."

The arguments have to stand on their own merits, not who I am. If they don't, they are failed arguments. Nevertheless, I offer this little biographical information simply as an overdue courtesy to all readers.

We have this conversational medium that supplants and transcends the quarterly journal, the roundtable, the privately published monograph; we are advanced readers; let's make the most of this.

Dudes, Doris rocks!

As someone who spent five years personally transcribing hundreds of hours of interviews for a recent oral history of Wall Street, you'll forgive me if I consider a noted and highly paid historian repeatedly committing plagiarism a serious crime of authorship. In my mind it's unconscionable that an institution like the New York Historical Society would be feting someone like Goodwin with awards and prizes after such disgraceful revelations, particularly when there are so many other historians and writers deserving of recognition.The comments after this post are remarkable. You see why I keep the comments feature on this blog turned off:

* "Dude, if you will just follow the links you yourself have provided, you will find out more information which I think does exonerate Goodwin to some degree."

* "Goodwin may have her faults, but she remains one of the most accessible, informative and reliable sources of historical insight in America."

* "I sense an ax to grind."

* "This seems to be more about the author's personal issues than what Doris Kearns Goodwin did or did not do."

* "As a long time Civil War/Lincoln fan, I found this book excellent- one of the top, if not the top, book about Abe that I have ever read. I have read hundreds."

* "I think it was inadvertence."

* "I actually have read the book and have recommended it to everyone with an interest in history."

* "In her case, it was not malice but confusion, like a song writer who discovers that a song he'd written was actually partly a tune he'd heard earlier and then forgotten about."

* "I just think Doris is wonderful!"

* 'So do you pronounce your name as "whiner?"'

* "I question your motives in raising this now."

* "You're quite off base here. Ms. Kearns Goodwin long ago acknowledged her mistake and has sought to do better."

The nonfiction reader has spoken: Dudes! Doris rocks!

(Upper right: receiving the Pulitzer)

It's no joke

Fortunately, not a Civil War author, though he might as well be in many cases. We must fail better.

4/04/2006

Shelby Foote, novelist

McClellan's "letters" - still a problem

I browsed a couple of new books recently and each referred to McClellan’s letters to his wife in exactly those terms - with not so much as a by-your-leave.

I browsed a couple of new books recently and each referred to McClellan’s letters to his wife in exactly those terms - with not so much as a by-your-leave.I decided to do a sanity check and spent about two hours rereading my notes from the Library of Congress’ McClellan Papers, W. C. Prime’s description in his book McClellan's Own Story, and Sears’ notes introducing his edited volume of Mac’s wartime correspondence. I then reflected on whether I was being prickly about scholars who use the expression “McClellan’s letters to his wife.”

My sanity checked out – if I may certify myself – and the phrase “McClellan’s letters to his wife” still stinks to high heaven. Can we not, therefore, add quote marks, an asterisk, a little authorial disclaimer? Here’s a passage that can follow the first reference to these “letters”:

As the author of this work, I use the expression ‘McClellan’s letters to his wife’ as a convenience to the reader and myself fully aware that these writings cannot be validated as actual wartime correspondence.If you want to write a longer note, have at it.

In January, I went to Princeton, where Max McClellan’s papers are kept. Max was the general’s son and Sears seems to have missed this family cache in researching The Young Napoleon (Max's papers are not cited in the edition of the work I have). I was looking for a letter from McClellan to his wife – it would be quite a catch because no one has ever seen a letter from McClellan to his wife authored during the general’s active service.

As far as I know, there are a couple of McClellan letters to Mary Ellen available from ’63 and ’64 but no one has seen such a thing from ’61 or ’62.

Among his papers, GBM left a small book about half the size of a modern photo album. He inscribed this book as containing notes he made from letters to his wife. We don’t know if he left out key text; or if he added text; or if he made changes to text. The “proof” we have that these are “true” copies rests entirely on assumptions.

With McClellan dead, W.C. Prime, editor of McClellan’s Own Story, found the book then went looking for the originals. At first he was told they had been burned.

He had no way of knowing whether or not they were burned. Nor do we.

Prime said that they turned out not to have been burned though he never saw them. He coquettishly declines to say directly where the unburned letters were found. We take his word that they existed when Own Story was compiled. Prime says through family help he enhanced GBM's notebook entries but does not disclose how he did that in his comments in the foreword to McClellan's Own Story. He makes no claim to having seen the originals.

Stephen Sears says, in his preliminary remarks in Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, that Prime worked a deal with May McClellan, the general’s daughter, who had access to the unburned letters. Sears says Prime asked May to read Mac's notes and then add material from the letters. The arrangement prevented Prime from seeing the letters. May, says Sears, took her father’s notes, added text to them, and returned them to Prime. We don't know what the methodolgy was. We don't know if she produced scraps attached to notes or if she rewrote each notebook entry. We don't know if she corrected her father's mistakes or changed to match the final, delivered form.

And we don't know where Mary Ellen McClellan fits into this transaction. We don't know how Sears knows about the Prime-May McClellan deal. Sears leaves no clue. If this happened as Sears described it, did May play straight with Prime? Did Prime honor May's input? How did he integrate the fragmentary new material? Had the letters really been preserved?

Based on Sears' unsourced description, we have May controlling the core editing process, handing Prime some kind of "finished product." The only way we can tell the difference between what was in McClellan’s notebook and what May and/or Prime added is if we compare the entries in the notebook with what Prime published in the posthumous autobiography, McClellan's Own Story.

That would be tedious - I've done it in this blog on a limited sample of letters. And what would that analysis yield? It would simply disclose the tissue of editorial overlay on notes of unknown provenance. (Prime, or Sears after him, could at least have used typography or markings to show us the difference between GBM’s notes and the writings that appear in McClellan's Own Story.)

So we have Prime being coy about the unburned letters and his amendments to McClellan's notes. We have Sears' word that May accessed unburned letters and that she consulted with Prime to amend the notes. More questions: did Sears make his own changes to the mysterious hybrid created by Prime and May? In a brief survey of Own Story matched against Sears' collection of correspondence, I found at least one unique, unexplained Sears redaction to Own Story and published it in this blog. (Sears had deleted McClellan's reference to his horse Kentuck.) Why would he do that? And why would a man supposed to be taking notes for a memoir include a trivial reference to his less favored mount?

So Sears revised Prime and/or May without having recourse to sent letters. (No one has recourse to the original material.)

The well of complexity is not dry yet.

Sears made the odd decision to priviledge the material in the letterbook over and above the writing ascribed to May. In comparing the Prime/May letters in McClellan's Own Story with the notes found in McClellan's papers, Sears made some amendments to Prime's allegedly May-enhanced material using the letterbook as a corrective. Let me put that more simply: May's alleged additions to her father's alleged letters were altered by Sears in some places based on giving primacy to Mac's notebook.

If May enhanced the notes found in McClellan's papers, if that is your (unsubstantiated) story, why would you give primacy to the letterbook over the later revisions?

Sears made more changes on even stranger grounds. Read this "clarification" and weep: "Where May McClellan copied more of a particular letter than her father had included, the letter has been reassembled based on context and on McClellan’s usual pattern of writing." [Emphasis added]

Reassembled. We began with a mysterious book and no letters; the book's entries are amended on the say-so of May McClellan, we are told; Prime works them over in ways we cannot guess at; Sears then revises Prime and May and “reassembles” some “letters” based on his own ideas about "patterns of writing" and "context" - all without recourse to sources.

Call me finicky but in circumstances like these, I demand quote marks and a footnote for “McClellan’s letters to his wife.” That's non-negotiable.

** [Edited on 4/5/06 for clarity.] **

** [Final edit on 4/6/06 for clarity.] **

p.s. A few personal observations on this notebook. If you have access to the McClellan Papers on microfilm you’ll notice some odd things about it.

First, many of the entries are written out fully – including conjunctions, prepositions, the lot – as if a first draft was being composed, not as if extracts were being collected for memoir writing or to refresh the memory.

Second, there are clauses crossed out as a thought changes. That is to say, Mac has made crossouts that are not copying errors but compositional errors – very improbable “copying” behavior, that.

Third, there is material here laboriously written out in his hand that has no value to a military memoir – the ostensible purpose for which “letters” were copied.

Fourth, there are the frequent omissions of place, date and time in the extracts. These are extremely valuable in reconstructing timelines. This is the whole point of extracting notes. Did Mrs. McClellan, in lending her letters to George omit the postmarked envelopes? Did the general neglect to guess at time and place of writing? Was May not able to fix the gaps?

Or are we dealing here with a first draft letterbook Mac later labeled as “notes”? You wouldn't need date, place, and time if you were going to send the letter later from a different location. Did his wife never actually loan him the (possibly burned) originals? Can these be reconstructions from memory or from loose copies of drafts?

We will never get to the bottom of this mystery until we can find a delivered letter to compare with Mac's notebook entries. I tried to find one and failed. I have an idea and I'll try again.

In the meantime, keep your ten-foot-pole handy when presented with "McClellan's letters to his wife."

[Stephen Sears responds to this post here.]

"Interpreting battlefields"

(Meanwhile, Kevin is displeased at my mischief of putting him at odds with McPherson's lifetime views on the origins of the war - and of using Ayers to do so.)

Let us fail better as we fail together

Reading McL's old English Lit stuff one marvels. And yet, these polished, scholarly works are nothing that anyone needs anymore - he is not cited in that field and his best work is long forgotten. His tentative media "probes" on the other hand continue to point the way towards a new sociology of communication. The transition for McLuhan - this is important - was fast, almost immediate.

Here's the counterintuitive part: his impact was through ephemeral media (e.g. TV appearances, symposia, lectures) that we can no longer access. Yes, we have a few books, but these were launching pads from which huge amounts of ethereal interactions followed. McL abandoned the safe and sane work of books, publishing, teaching, for argument in the moment. If his career is a study in the transmission of ideas, we have something important to learn in Civil War circles. Particularly within this Internet.

After several false transformations (trying to cross over into television and films) our Civil War culture has reached a switchpoint. But where McLuhan could suddenly see culture being conveyed and transformed in all sorts of media, we continue to rivet our attention to the book as conveyance of choice. Edward Ayers tried to nudge us forward into his Valley of the Shadow but we were not prepared to walk with him - and that project ultimately became (sigh) another book.

Let me rephrase that. A terribly important and famous ACW Web project became a boring and predictable print media artifact. On some level, someone told Ayers his project was a failure if it simply stayed on the Web.

My friends, we can fail much better than to release another book to small sales into a confused and ignorant marketplace. If we apply ourselves, we can fail most excellently indeed.

And what is this world of nonfiction trade publishing anyway? It is a world in which sales levels cow scholars, where the size of a public following conveys a "truth" that floats free of sources, free of argument, free of new discoveries. It is a self-limiting scandal, a harlot to entertain us by the fireplace or on the beach. A harlot that demands, oddly, to be taken seriously.

Drinks with Tim

Tim Reese and I were having a beer in Ball's Bluff Tavern, Leesburg, a few weeks ago when the talk turned, naturally enough, to failure.

Tim has one foot in the Web and another in books. Tim was nudging me towards publishing "that book" and I was nudging back: "Put everything you have on the Internet," I said. "You are the expert on Crampton's Gap and the Lost Order - everyone will find your stuff who searches the Web. Your material trumps every written work to date. You are empowering the student to know more than the professor. You are empowering the reviewer to correct the next hack's Maryland Campaign history. You can have a lasting effect without losing money or suffering in the expectations game."

Well it went something like that. But then I saw Moe last week and he said Tim told him to tell me to get that book going, so maybe my arguments were not as clear as remembered.

My dinner with Moe (and Wanda)

Moe Daoust and I were co-founders of the McClellan Society online; he and his wonderful spouse Wanda were in Leesburg last week - down from their home in Western Canada. Over some nice wine and 18th Century American cooking - the specialty of the house at the Green Tree restaurant - Moe urged me to get "that book going."

Later this year, Moe is going to have an article published in a Civil War glossy that represents years of research. It will play havoc with our understanding of events at Burnside's Bridge. He seemed kindly disposed towards the world of print.

I tried my Intenet arguments out on him. "You know too much about McClellan," was his rejoinder, if I recall. Books don't have an impact, books don't make money, I think I said. Moe and Wanda said it was more about getting it down, out of the head onto paper.

"I'm going to stay on you until we have that book," he promised, his very words on parting.

Towards a manifesto

I may write a book. I'm thinking about it. But I don't feel obliged to do so.

Can this blog be a book substitute? I think it can. It requires a leap of faith, perhaps, over the bound book culture. It requires a dispensation: "He's not being lazy or unfocused."

Can pathbreaking research be published on the web? I think it must be. The least we can have from copyrighted work is summary and conclusions.

Given the painful transition out of print technology, the decline in the Civil War publishing model, and the accessibility of web publishing to everyman, it seems to me we can all fail better, much better, on the Internet.

Can that be my credo?

(Hat tip to Tim, Moe, Wanda, Eric, Marshall, and Malcom McLaren)

4/03/2006

Kevin Levin on HNN

I agree with the late historian William Gienapp that the "outbreak of war in April 1861 represented the complete breakdown of the American political system. As such the Civil War constituted the greatest failure of American democracy." I wish more people would approach the study of the Civil War from this perspective.

"Complete breakdown" - it's the reasonable and natural argument. Kevin should prepare himself for the counterblast: "irrepressible conflict," "inevitability of sectional conflict," "one nation cannot remain half free and half slave," etc. I'll be watching HNN for these Hegelian counterarguments.

Randall once mocked them handsomely. Looking at contingency in history he told the AHA, no less: "Suppose such a war had happened—for instance, a misguided war between the United States and Britain in the 1890’s concerning Venezuela. One can imagine the learned disquisitions that might have poured forth to 'prove' that that Anglo-American war was 'inevitable.'"

Kevin makes the interesting observation that we look at the nightly news and its parade of foreign civil war horrors as tragic and regressive - no upsides there. Yet in considering our own history, we lapse into this national satisfaction.

The Whiggish historians interpreted English history as a march of progress with setbacks on the way. The American Whigs, foremost among them James McPherson, follow suit. The nation is better, stronger, more just, more united after this awful but inevitable bloodbath.

Let me quote Edward L. Ayers from an earlier posting here:

The current [ACW] interpretation contains these tensions in an overarching story of emergent freedom and reconciliation. While acknowledging the complicated decisions people faced, Burns and McPherson resolve these through narrative.And of course, you cannot resolve deep questions of history and philosophy through storytelling or literary devices. More Ayers:

McPherson is so vigilant [in protecting his conclusions] because he recognizes that this interpretation [that he champions] has become established only after a long struggle. The elegance and directness with which he and Burns tell their stories can lead us to forget what a complicated event the Civil War was.Finally, Ayers once more:

While vestiges of older [ACW] interpretation still crop up in people's vague recollections, no one has stepped forward in a very long time to offer a popularly accepted counterargument to the explanation codified in Burns and McPherson.Kevin has done so, and in the lion's den of HNN. Let's see how vigilant McPherson and friends remain in quashing this "older interpretation" of the origins of the ACW.

4/01/2006

A "new media" centered Civil War Blog

Speaking of AotW, Brian has absorbed Tim Reese's Crampton's Gap website lock, stock, and barrel - that's a good home for it. Sensible digital consolidation.

p.s. In an earlier "new blogs" posting I made a bad link to Andy Etman's new site. Here it is corrected.