Maurice D’Aoust has written to respond to this guest post:

Before I address Mr. Sears's comments (guest post 3/25/2014,) I think it would be worthwhile pointing out a few facts. As I’ve previously mentioned, by itself, Lincoln’s 12 Midnight copy of McClellan’s telegram proved nothing other than the fact there were two versions of the September 13, 1862 communication. Hence why I sought out supporting evidence which I knew would be necessary if Lincoln’s copy was to have any hope of taking precedence over the War Department's (Official Records) 12M version.

Ultimately, three very strong pieces of evidence were uncovered that, in combination, went far in disproving the notion McClellan was (1) aware of the Lost Order just before noon that day or (2) that he could possibly have sent that telegram to Lincoln at "12M". First there were the two primary source accounts, one being furnished by Dr. Tom Clemens, confirming that Barton Mitchell, the Lost Order’s discoverer, did not even reach Frederick with his regiment until noon on the 13th. When considering all of the steps that would have had to take place after Mitchell broke ranks (making his way to the recently abandoned Rebel encampment, finding Lee’s Lost Order, the time it would have then taken for the document to make its way through the various headquarters etc., etc.) it becomes clear that it would have been impossible for the Lost Order to have reached McClellan anywhere near noon. It simply does not make any logical sense. The second piece of evidence negating the 12M or noon version of the telegram was contained within the message itself when McClellan states, “we have possession of Catoctin. By “Catoctin,” the General was referring to the mountain pass over the Catoctin range, west of Frederick. According to all accounts, that defile was not taken until 2 p.m. on the 13th, a full two hours past “12m” [noon]. At this point, it becomes quite clear that the time-stamp on the Official Records version is wrong.

The above evidence was presented in my “McClellan Did Not Dawdle” article (

Civil War Times, October, 2012 issue.) Mr. Sears forwarded a rebuttal to Civil War Times and this together with my own response, were published in the December issue. Never, either in his

Civil War Times response nor in this latest rebuttal, has Mr. Sears ever addressed or even acknowledged that evidence. This only leads me to conclude that he simply has no answer. In truth, there is no answer other than to concede that the Lost Order could not have reached McClellan before noon and neither could that message to Lincoln have been written at "12M [noon]."

Of course, all of this alters the timeline of events on September 13th. According to Sears, the clock had, by virtue of a supposed “12M” message, started ticking at noon. In light of the 12 Midnight document and the strong evidence supporting it, that starting time must now be shifted to 3 p.m., when McClellan makes his first written reference to the Lost Order in his communication to Alfred Pleasonton. On that note, if a supposed 12M reference was good enough for Sears and others to prove that the Lost Order was in McClellan’s hands shortly before noon, why should an alternate 3 p.m. reference not be sufficient in proving it must have reached him shortly before 3 p.m.? When viewed in that context it can no longer be argued that McClellan sat on the information for over six hours before acting on it. Quite to the contrary, it is now clear that he acted with due diligence by promptly sending his cavalry forward to confirm its contents. What time it was when Pleasonton returned is unknown. Some say six p.m. but it's safe to imagine that the reconnaissance would have taken anywhere between one and a half to three hours. By 6:20 p.m. McClellan had formulated his plan and issued his first formal orders to Franklin. Contrary to what Mr. Sears would have us believe, McClellan had not allowed those afternoon hours of September 13th to slip away. In fact, including preparations for the very crucial action on Catoctin Mountain, assessing the information on the Lost Order, ordering Pleasonton forward, devising his plan, drafting his orders to Franklin and a variety of other military concerns, McClellan had things well in hand that afternoon.

For ease of reference, I’ve addressed each of Mr. Sears’s points individually.

THE DEBATE

SEARS: The issue: Did McClellan send his telegram at noon or at midnight on Sept. 13?

D'AOUST: The evidence presented is overwhelming in proving it was sent at Midnight.

SEARS: The point of it all: How and when and in what form did McClellan respond to the remarkable discovery of Lee’s campaign plan?

D'AOUST: The point of my

Civil War Times article was (1) to prove that McClellan's telegram to Lincoln was sent at Midnight (2) that it was nowhere near noon when McClellan came into possession of Lee's Lost Order and (3) that he did not allow any time, let alone some six-plus hours, to slip away that afternoon. As such, my comments in this debate will be restricted to those aspects only.

SEARS: Here are all the facts relating to this telegram that I have been able to verify.

(1) The sending copy, important enough to be certainly in McClellan’s hand, sent from Frederick, Md. to Lincoln in Washington on Sept. 13, is not on record.

D'AOUST: Acknowledged, but it appears we may now have the next best thing. See 7 below and Appendix A in this regard.

SEARS: (2) The primary copy of McClellan’s telegram is therefore the copy made by the operator at the War Department telegraph office. It is dated Sept. 13 and time-marked 12M. It is in the National Archives, Record Group 107, Microcopy 473, Roll 50. It bears the stamp of the Official Records compilers. Call it the Archives Copy.

D'AOUST: Mr. Sears chooses to believe that the War Department or Archives Copy was the primary or first transcription of the message after it was deciphered by the telegrapher. In fact, it makes considerably more sense that Lincoln’s copy would have been the first to be transcribed. After all, the communication was addressed to the President who was then anxiously awaiting news from McClellan and the telegrapher would certainly have been aware of the importance in getting the message to Lincoln post haste. For all we know, Lincoln was standing beside the telegrapher when the message came in, he being known to frequent the telegraph room into the late hours of the night in such high drama situations. In any event, it simply doesn’t make sense that the telegraph office employee would have delayed getting the message to an anxious Lincoln by first performing a clerical function such as making a copy for the War Department files. Finally, just because a document is in the National Archives does not mean it is factual. There are many examples of erroneous documents in the National Archives, McClellan’s September 11, 1862 "12M" telegram (yes, another one) to Henry W. Halleck being a prime case in point. Again, see 7 and Appendix A below in this regard.

SEARS: (3) The manifold, or carbon copy of the Archives Copy is in the Seward Papers, University of Rochester. It is of course identical to the Archives Copy (including the 12M time-mark) except no Official Records stamp. This carbon is important because it identifies which of the operator’s copies is the primary copy (above). Call it the Seward Copy.

D'AOUST: Clearly the Archives’ copy is erroneous, as are all other copies made from it, including Seward's. An “Official Records stamp” does nothing to alter the fact a document is invalid. Again, please refer to the McClellan/Halleck message in 7 and Appendix A below.

SEARS: (4) Having made an original and carbon, the War Department telegraph operator made a copy for Mr. Lincoln, the addressee. It is a fair copy, careful written, in a slightly different format. It is time-marked 12M in the telegrapher’s hand. In another hand, 12M is altered to 12 Midnight, i.e., 12M + idnight. (This alteration is clearly seen on the microfilm and clear enough on the digitized version.) This copy is in the Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress. Call it the Lincoln Copy.

D'AOUST: Again, why would the telegrapher have taken the time to perform a clerical function (making an "original and carbon" copy for the War Dept. files) before getting such an urgent message to Lincoln? It does not make any sense. As for the “idnight” aspect, I believe the more proper term would be “amended,” that is to say, "corrected to reflect the true facts of the matter."

SEARS: (5) The Sept. 13 telegram was first printed a year later, in 1863, in the

Report of the Committee on the Conduct of the War, copied from the Archive Copy supplied by the War Department and marked 12M. It was published in the Official Records (19.2:281) in 1887, from the OR- stamped Archives Copy and marked 12M. It is published in my The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan (1989) p. 453, transcribed from the Archives Copy and marked 12M.

D'AOUST: How does all of this, in any way, alter the fact the 12M "Archive Copy" as well as any reproductions or printings thereof are all incorrect? Do ten, twenty or one hundred “wrongs” make a right? Obviously, no one was aware of Lincoln’s copy and the fact it stipulated 12 Midnight. Until recently at least, only a few thought to question or look into the matter.

SEARS: (6) The Lincoln Copy of the telegram was sequestered for 95 years, in the president’s papers until 1865, then held by Robert Todd Lincoln and donated to the Library of Congress, and opened to the public in 1947. (I came upon the Lincoln Copy—surely not the first to do so—on Lincoln Papers microfilm about 30 years ago when researching my McClellan biography and McClellan Papers. It posed a puzzle. I applied to it the same tests I’ve outlined here and concluded it was an anomaly, not historically viable.)

D'AOUST: It’s that part about this whole issue that really bothers me. If Mr. Sears did come across the document some thirty years ago, what gave him the sole right to conclude it was “an anomaly not historically viable” and then suppress it? At the very least, he should have disclosed its existence if only to allow others to apply their own "tests" in determining the document’s validity. Had he done so, I’m certain someone would have solved this "puzzle" long ago.

SEARS: (7) 12M is the abbreviation for 12 Meridian, or noon, standard in Civil War telegraphy. 12M is not a standard abbreviation for midnight in Civil War telegraphy or anywhere else. (I have 22 examples of McClellan 12M telegrams, nearly all in his hand; 14 by content or received time are explicitly noon. The rest are neutral as to time; none implies midnight.) When McClellan meant noon on a telegram he marked it 12M. Always. McClellan never time-marked 12 Midnight on a telegram.

D'AOUST: And here is where Mr. Sears has made his greatest mistake. Gene Thorp of the Washington

Post and Tom Clemens (Editor, Ezra Carman Papers,) recently uncovered a sent copy of a telegram from McClellan to Henry W. Halleck dated September 11, 1862 and time-marked 12 Midnight. So much for McClellan never time-marking 12 Midnight on a telegram. But things get considerably better. Thorp and Clemens then compared that sent copy to the National Archives’s “received” copy (yes, the “primary” War Department copy on which that “Official Records” stamp was affixed and yes, the same copy that we see today in the Official Records.) And what time-stamp does this Official Records copy stipulate? 12M! The details surrounding Thorp's and Clemens's amazing piece of historical research is described in Appendix A below.

SEARS: (8) Who altered 12M into 12 Midnight on the Lincoln Copy? (Somebody did!) I’ve concluded it had to be Mr. Lincoln himself. The handwriting is not inconsistent with Lincoln’s. This telegram, and others that day, were much delayed by wire-cutting Confederates in Maryland. It is marked received 2:35 a.m. Sept. 14, or 14:35 hours late. Seeing it early on Sept. 14 with that received time, unaware of the telegraphic delay, Lincoln decided it must have been sent at midnight and so marked it. There is no reason to think Lincoln was especially familiar with telegraphy protocols. We forget that generals (except McClellan) did not telegraph the president from the battlefield—they followed the rules and sent to the War Dept. or Army HQ.

D'AOUST: We can postulate all day long regarding who may have “amended” the time stamp but in the final analysis, whoever did add the “idnight” obviously did so because they knew that 12 Midnight was the correct time designation and the evidence proves that they were correct.

SEARS: (9) For this telegram to have been sent at midnight on Sept. 13 requires a scenario like this: a) McClellan time-marked the sending copy 12 Midnight, something he had never done on a telegram and knew better than to do. b) The War Department operator, instead of time-marking his copy (with carbon) 12 Midnight as he was supposed to do, instead wrote 12 M—which c) was the dead-wrong abbreviation for midnight. d) Then “somebody” else—who could it be?—“corrected” the copy for the president by adding “idnight,” but e) did not “correct” the file copy and carbon. Theater of the absurd.

D'AOUST: At this point I think it best to refer Mr. Sears to Gene Thorp's description of events in Appendix A below. The bottom line is, there are no theatrics involved here but rather sound reasoning supported by overwhelming evidence.

SEARS: (10) In sum, the documentation is unassailable for a noon telegram, non-existent for a midnight telegram. No effort to argue that somehow it was physically impossible for McClellan to write this telegram at noon meets evidentiary standards. The three documents in and of themselves trump any and all alternate theories. Mr. D’Aoust and compatriots start with this supposed midnight telegram, then bend and twist and warp trying to make it fit the documented facts. It doesn’t and can’t. They are left with an anomaly.

D'AOUST: By documentation, I'm assuming Mr. Sears is referring to the War Department copy on which that "Official Records" stamp has been affixed, the same stamp as was placed on the War Department copy of that September 11th message to Halleck, which we now know for certain to be incorrect. Or is he referring to the various carbon copies on which the error is repeated over and over again? Are these also the "documents" that supposedly trump all alternate theories? I don't mean to be flippant but the idea that some officious stamp would automatically render a document more valid than another truly is “theatre of the absurd.” As for "evidentiary standards," Mr. Sears seems bent on ignoring the conclusive evidence surrounding the 27th Indiana's arrival time and that surrounding the Catoctin aspect. Will he also ignore Thorp's and Clemens's corroborating, albeit circumstantial, evidence surrounding the September 11th message to Halleck? With all due respect to Mr. Sears, it is he who is warping the facts to fit with the clearly flawed "12M" telegram.

SEARS: (11) Finally, and as important as anything else, simply read McClellan’s exuberant, almost giddy noon telegram in the context of Sept. 13’s events. See especially his 11 p.m. telegram to Halleck (OR 19.2:281-82; McClellan Papers, 456-57). No exuberance now, much worry, he is outnumbered, etc. He would never have sent his Lincoln telegram an hour later; that’s a sequence that simply makes no sense. (In this 11 o’clock telegram McClellan says he was handed the Lost Order “this evening.” What he meant by that is that cavalryman Pleasonton, who was sent a copy of the Lost Order at 3:00 p.m. [OR 51.1:829], had that evening confirmed that the find was authentic.)

D'AOUST: As for the variance between Halleck's and Lincoln's telegrams, upon reading Halleck's communication in its entirety it becomes evident that McClellan's intent was to communicate the critical nature of the situation and thus prompt Halleck, his immediate superior, into releasing the two corps that were still sitting idle in the Washington area. McClellan likely surmised that Halleck would communicate this to Lincoln. Although less gloomy, McClellan's message to Lincoln still conveys the critical nature of things. Mr. Sears is reading way too much into these two communications and this to the extent of making himself appear to be grasping at straws which he does yet again in his "this evening" theory. In that regard, as pointed out in my opening commentary, having discounted the 12M version, McClellan's message to Pleasonton now becomes his first written allusion to the Lost Order thus implying that the order fell into his hands shortly before 3 p.m. As I pointed out to Mr. Sears in our

Civil War Times exchange, Websters' Dictionary defines "evening" as "the entire late afternoon" or "the latter part of the afternoon and the earlier part of the night." It would seem McClellan considered the 3 p.m. as falling within Webster's definition and he wouldn't have been far off.

SEARS: Certainly, absolutely, there is room for discussion and debate as to McClellan and the Lost Order. What action did he take? When? What should/could/ought he have done? What could he not do? And so on. For General McClellan, the clock on all those matters began ticking at noon on Sept. 13. I would suggest that anyone interested in the topic start their own clock ticking at noon.

D'AOUST: I won't cloud the issue by entering into a discussion on would'a could'a or shoulda's. On the other hand, I do urge any who read this exchange to look at the evidence, both Mr. Sears's and mine, objectively in determining whether a) McClellan's telegram to Lincoln was sent at 12M [noon] or 12 Midnight b) whether it was anywhere near noon when McClellan came into possession of the Lost Order and c) whether McClellan allowed any time, let alone some six-plus hours, to slip away that afternoon. I'm confident that the majority will, after weighing the evidence, conclude that the telegram was sent at midnight, that McClellan did not learn of the Lost Order until well after noon, likely closer to 3 p.m. and that he wasted no time that afternoon.

***

Appendix A: The September 11, 1862, 12 Midnight telegram from McClellan to Halleck

[Editor's note: Italicized text by Gene Thorp: editorial text by Maurice D’Aoust. The first image is figure 1, the lower image is figure 2.]

Although Dr. Clemens deserves to share in the credit for the following discovery, he insists that Gene Thorp deserves the bulk of that credit, having conducted most of the groundwork. Here now are the details surrounding Gene Thorp’s and Tom Clemens’s discovery, as described by Thorp:

In short, when the Sept. 13 telegram came out of cipher at the War Department, an operator misinterpreted 12 Midnight as Noon. Although [we don’t] have McClellan's original Sept. 13 telegram, I can prove conclusively that this exact same mistake was made two days earlier (Sept. 11) by the exact same War Department operator.

Here's what happened.

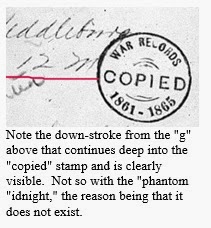

1. On Sept. 11, McClellan telegraphed [Henry W.] Halleck from his headquarters in Middleburg, MD at 12 Midnight. [See McClellan’s “sent” copy, figure 1, right. Click to enlarge.]

2. At the War Department, an operator deciphered the message, and in the process, misinterpreted the time-stamp writing 12M instead of 12 Midnight on the decipher worksheet. (The deciphered worksheet is not found.)

3. The same operator then made a copy from the worksheet, on War Department heading, and sent it to the recipient, Gen. Henry Halleck. This copy was incorrectly time-stamped 12M. [See Figure 2, below.]

4. Later an operator, or transcriber, used the misinterpreted decipher worksheet to make War Department file copies. One was in original handwriting, the rest were carbon copies. All of these copies were incorrectly time-stamped 12M.

5. Years after the war, officials compiling the Official Records located one of these War Department file copy carbon copies. Not having access to McClellan's papers, the officials transcribed the information from the [incorrectly time-stamped] War Department file copy carbon copy. They then stamped it with the red "War Records copied" stamp and wrote in green pencil "Printed [that is, printed in the Official Records]."

6. The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion were printed and in every single instance, the time-stamp of 12 M was used even though the original message [McClellan’s sent copy] said "12 Midnight".

And so it remains incorrect today. Any historian consulting the Official Records without consulting McClellan's original Sept. 11 telegram first will inadvertently duplicate this error. They will write that McClellan sent the telegram at noon and it was received at the War Department 13:45 hours later, when if fact it was actually sent at midnight and received only 3:45 hours later.

This exact same sequence, with the exact same War Department operator, happened two days later on Sept 13. The only difference is that someone caught the mistake on Lincoln's received copy and corrected it, thus the odd handwriting for "idnight."

Rinse and repeat

1. At 12 Midnight on Sept. 13, after writing marching orders to all his different Corps for the next day and informing General-in-Chief Halleck of everything that had transpired, McClellan sent a telegram to Lincoln announcing he had possession of Lee's plans. McClellan was responding to a query from Lincoln earlier in the evening that had been sent via telegram to Point of Rocks and then transmitted by signal to his headquarters north of Frederick. (The Signal Corps OR report states this. Neither the Lincoln or McClellan original has yet been found.)

2. At the War Department, the same operator as two days before deciphered the message, and in the process, misinterpreted the time-stamp writing 12M instead of 12 Midnight on the decipher worksheet. (The deciphered worksheet is not found.)

3a. The same operator then made a copy from the worksheet, on War Department heading, and sent it to the recipient, President Lincoln. This copy was initially incorrectly time-stamped 12M. Note [that]the handwriting is of the same operator that wrote Halleck's recipient copy.

3b. Unlike Sept. 11, either the operator, his manager, or perhaps even Lincoln himself corrected the time-stamp to read "12 Midnight." The operator or his manager could have seen it was deciphered incorrectly or Lincoln may have known because he was waiting for a response to the telegram he had sent McClellan earlier in the evening as is recorded in the Official Records.

4. An operator or transcriber used the misinterpreted decipher worksheet to make War Department file copies. One was in original handwriting, the rest were carbon copies. All of these copies were incorrectly time-stamped 12M.

5. Years after the war, officials compiling the Official Records located one of these War Department file copies. Not having access to McClellan's papers or Lincoln's papers, the officials transcribed the information from the War Department file copy carbon copy. They then stamped it with the red "War Records copied" stamp and wrote in green pencil "Printed.”

6. The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion were printed. In every single instance, the incorrect time-stamp of 12 M was used.”

Since the discovery of Lincoln's 12 Midnight version of the telegram and the overwhelming evidence supporting it, historians such as Tim Reese, Tom Clemens and Scott Hartwig have, via their respective publications, been chipping away at the long standing myth wherein McClellan wasted six hours after coming into possession of Lee's Lost Order. It's hoped that Clemens's and Thorp’s amazing piece of historical research will encourage even more historians to join in and that eventually, the 12M myth will be completely dispelled.